Sea-lebrating 40th anniversary of mass coral spawning discovery

Categories

Share

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2021/Must-credit-Peter-Harrison---plate-corals-spawning-17-Nov-2019-small-PH8_4071-720px-720X475.jpg)

Of the millions of new scientific research papers published every year, some discoveries are simply awe-inspiring. Like the first observation, in 1981, of one of the world’s greatest natural spectacles: how the Great Barrier Reef’s corals create new life.

There to bear witness and document the remarkable phenomenon of many species of corals synchronously releasing millions of eggs and sperm bundles in a mass kaleidoscopic-coloured orgy was Southern Cross University’s Distinguished Professor Peter Harrison, then a young PhD researcher.

That eureka moment transformed global understanding of sexual reproduction and was the start of Professor Harrison’s fascination with the breathtaking beauty of this annual underwater snowstorm as the coral sperm and eggs float to the surface of the ocean to fertilise and develop into larvae.

CHARLIE VERON: Until recently it was believed that corals brooded their planulae inside their bodies. With majority of corals this isn't so as a group of marine biologists from James Cook University have found out. What they have discovered is one of the most spectacular sites to be seen on the Great Barrier Reef. Peter come and tell us about it.

PETER HARRISON: We now know that the majority of corals on the Great Barrier Reef don't brood their larvae but instead shed their eggs and sperm into the sea for external fertilization. What is so exciting is that thousands of corals on the Great Barrier Reef are many different reefs spawn together on only a few nights of the year and amazingly enough we can now predict when the spectacular mass spawning will occur.

There are three main cycles that appear to synchronize the mass spawning. They are the setting of the sun on spawning night, the monthly lunar cycles and the annual sea temperature pattern on the Great Barrier Reef. If we take this staghorn coral as an example the tiny eggs within each polyp are nurtured and grow throughout the year. When the sea water warms at the end of the tropical winter sperm are produced.

As the spawning night approaches the eggs become coloured and the sperm become active. On the spawning night itself the eggs and sperm are bundled together within the body of each polyp. The bundles are about one to two millimetres across and are slowly rotated within the polyp and then squeezed through the mouth.

Sometimes the bundle is held by a thin strand of mucus until it breaks free and floats to the surface. Suddenly many polyps begin releasing simultaneously until the whole colony is spawning as shown in this simulation. The egg and sperm bundles then float to the surface where they break apart spraying egg and sperm clouds throughout the water.

Under a microscope we can see sperm searching for an egg to fertilise. Once the egg is fertilised it begins to divide in half and this cell division process continues throughout the next day until what scientists call a planular larvae is formed. This planula grows tiny hair-like cilia which beat together and allow the planula to move. At first the planula is a round blob rotating on the sea surface but over the next few days it becomes more active and is firstly a pear-shaped and finally in elongated form.

The planulae of most corals develop in the sea over three to six days this means that they are likely to be swept off their parent reef and into the vast ocean currents where they may be carried for weeks amongst the plankton. It is at this time that the planula are at their most vulnerable they have to face many hazards from hungry planktonic predators to violent tropical rainstorms.

On one occasion we observed millions of eggs being destroyed when a particularly violent rainstorm coincided with the mass spawning on a reef near Townsville. Few planula that have been lucky enough to survive drift onto a new reef and head for shelter. The pleinuli starts searching for a place to settle and at this stage are at the mercy of predators such as fish, crabs and other corals. Only a tiny proportion make it to this stage those that do then turn into a polyp by a process of metamorphosis. The juvenile coral polyp now begins to secrete a skeleton and if it's able to survive a new colony will form and the life cycle is complete.

It was spring 1981 at Magnetic Island, off the Central Queensland coast near Townsville. Serendipitously, a few months earlier, the United Nations had declared Australia’s Great Barrier Reef a World Heritage Area based on its ‘outstanding universal value to humanity’.

Four decades on and the Great Barrier Reef’s iconic status remains. It is one of the seven natural wonders of the world and the largest living structure on the planet – so immense it can be seen from space.

“Forty years ago, I was part of the young team of PhD coral researchers at JCU working on the central Great Barrier Reef that discovered the mass multi-species coral spawning phenomenon,” recalls Southern Cross University’s Professor Harrison who’s been in the Whitsundays for the initial part of the 2021 spawning season.

“Our first records of multiple species spawning together occurred on 18 to 21 October 1981 at Magnetic Island, off Townsville.

“On cue, some corals on the inshore warmer reef areas, like here at the Whitsundays, spawned together within a few nights, on the same lunar phases after this year’s October full moon.

“Our collaboration highlights how important it is to work together to discover new things about this extraordinary and beautiful planet we share and hopefully apply that knowledge to manage it much better in the next 40 years.”

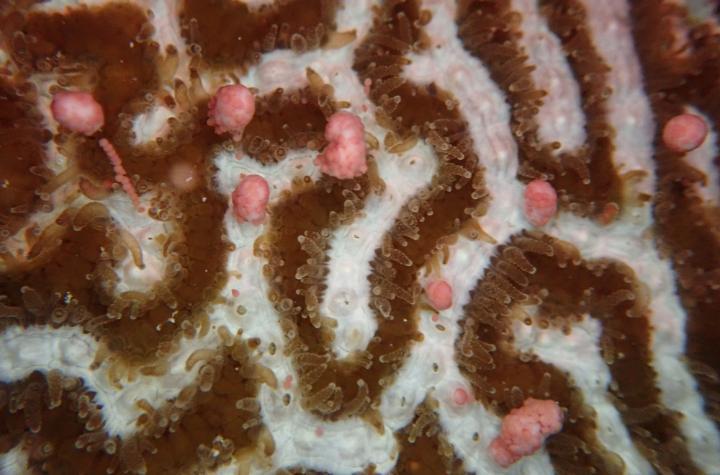

Close up of platygyra daedalea coral spawning. Note the pink-coloured egg and sperm bundles being released (credit Peter Harrison).

Three years later, in 1984, the team’s groundbreaking research was published in the journal Science: 223: 1186-1189.

Mass Spawning in Tropical Reef Corals (1984)

By Peter Harrison, Russell Babcock, Gordon Bull, James Oliver, Carden Wallace, Bette Willis.

Abstract

Synchronous multispecific spawning by a total of 32 coral species occurred a few nights after late spring full moons in 1981 and 1982 at three locations on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. The data invalidate the generalization that most corals have internally fertilized, brooded planula larvae. In every species observed, gametes were released; external fertilization and development then followed. The developmental rates of externally fertilized eggs and longevities of planulae indicate that planulae may be dispersed between reefs.

The Australian scientific community later recognised the team with a Eureka Prize.

Eureka Prize for Environmental Research 1992 awarded to the Coral Spawning Team

Awarded for one of the most exciting discoveries made in coral reef biology, an annually synchronised spawning activity on the Great Barrier Reef on more than 100 species of coral, a sexual synchronisation which is unknown in any other part of the Animal Kingdom.

Likened to an upside-down snowstorm or a gigantic marine fireworks display, our knowledge and understanding of this biological event has been developed by young scientists from James Cook University. Its biological and aesthetic fascination has caught the attention of the scientific and lay press throughout the world and featured widely on film, in the electronic and print media and through public lectures given by various members of the team.

Each year during spring and early summer Southern Cross University’s Professor Harrison returns to the Great Barrier Reef for the annual underwater spectacle. The epiphany back in 1981 - witnessing coral reef systems replenish en masse - forever changed him.

Devoting his life’s work to reef ecology and coral reproduction, Professor Harrison has spent many years developing and refining a novel coral larval restoration technique, now known as Coral IVF.

“Following our discovery, while swimming through coral spawn slicks at night, the larval restoration concept came to me: by collecting some of these developing embryos we could grow millions of larvae that could be settled back onto damaged reef areas to catalyse the recovery of coral communities,” he said.

Professor Harrison and his team – many of whom are Southern Cross University PhD students – collect just a tiny fraction of the trillions of eggs and sperm released during spawning, nurture them in floating larval pools on the ocean surface until they develop fully into coral larvae, then release them onto damaged sections of reef.

Coral IVF has been used successfully in the Philippines and more recently on the Great Barrier Reef; and has restored breeding coral populations on damaged sections of reefs.

Southern Cross University’s Distinguished Professor Peter Harrison is in the Whitsundays for coral spawning of the inner reef colonies in October; and at Lizard Island, northeast of Cairns, in November for the outer reef spawning.

Professor Peter Harrison measuring coral larvae concentrations as part of the Coral IVF technique.

Media contact: Sharlene King, media office at Southern Cross University, 0429 661 349 or scumedia@scu.edu.au

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/images/Coffs-harbour_student-group_20220616_33-147kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/services/counselling/images/RS21533_English-College-Student_20191210_DSC_6961-117kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/scholarships/images/STEPHANIE-PORTO-108-2-169kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/arts-and-humanities/images/RS20958_Chin-Yung-Pang-Andy_20190309__79I5562-960X540.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/experience/images/SCU-INTNL-STUDY-GUIDE-280422-256-72kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/dep-site-assets/component-library/screenshots/online-1X1.jpg)

/250x0:1250x1000/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/Todd_Thimios_Cocos_Island_Ultimate_Dive_Sites.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/Humpback-whale_credit-Aurore-Murguet-on-Pexels-2000X973.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/Dog-labrador-with-a-stick_credit-Mitchell-Orr-on-Unsplash-2000X973.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/yasmeen-2.png)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/Sydney-Rock-Oyster-lease-credit-Southern-Cross-University-2000X973.jpeg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2023/Shucked-oysters-02_Southern-Cross-University-2000X973.JPG)

/379x0:1352x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Mahmoud-Abu-Saleem-Andrew-Rose-Joe-Gattas-on-verandah_2024-Dec-3_03-2000X973-135kb.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Peter-Harrison-Acropora-valida-spawning-Heron-PH-PC050158-2000X973.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Nigel-Andrew-gives-keynote-address-at-AES-Conference_2024-Nov-20-2000X973.jpg)