School of fish: how we involved Indigenous students in our investigation of a 65,000-year-old site

Share

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2020/The-Conversation-indigenous-fishing-720X475.JPG)

Morgan Disspain, Southern Cross University and Lynley Wallis, Griffith University

A recent program for school kids in Kakadu and West Arnhem Land, incorporating traditional knowledge and Western science, is a model for teaching Indigenous children on Country.

The Djenj Project (djenj means “fish” in the local language) involved teaching Bininj (Aboriginal) children and rangers about fish, and scientific water research techniques, to improve employment opportunities.

As archaeologists, we wanted to find out how fish populations near the 65,000-year-old Madjedbebe archaeological site have changed over thousands of years. Evidence collected from the rock shelter suggests it’s one of the oldest sites on the continent.

We wanted to know which fish Bininj inhabitants at the site ate in the past, where and how they caught them, what the environment was like then, and what impact humans and environmental change have had on fish populations.

We needed to gather information about traditional fishing methods and knowledge. We also needed to gather samples of the current fish in the region, to compare them with fish remains excavated from Madjedbebe.

Read more: When did Aboriginal people first arrive in Australia?

To do that meaningfully, we wanted to bring the community on the journey with us, rather than working in our labs in isolation. Dozens of school children between the ages of seven and 17 were involved in the project. They helped us answer our questions and learnt a lot in the process.

Beyond thinking about our scientific aims and questions, we put community-based benefits at the forefront of the research process. At the heart of the project were the core ideas of respect and two-way knowledge sharing, especially giving senior Bininj people the opportunity to share their knowledge and skills.

What it looked like

The project included about 80 community members from the small townships of Jabiru and Gunbalanya, and surrounding outstations in the Top End of the Northern Territory.

Bininj Elders shared traditional ecological knowledge with Bininj children, rangers (the Djurrubu Rangers of Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation and Njanjma Rangers), and Western (Balanda) researchers. Everyone worked together to prepare teaching resources so the project has long-lasting benefits.

Fishing is a favourite activity for Bininj, so participation in the project was high. While word-of-mouth was the main way to reach the community about catching fish for the project, we also shared short videos on social media. These explained what we were doing and how people could get involved.

One positive side-effect of the project was providing large amounts of fish for the community to eat, promoting healthy eating.

In between the fishing and the eating was the science and the learning. A key aim was to integrate cultural knowledge into school lessons to improve literacy and numeracy skills.

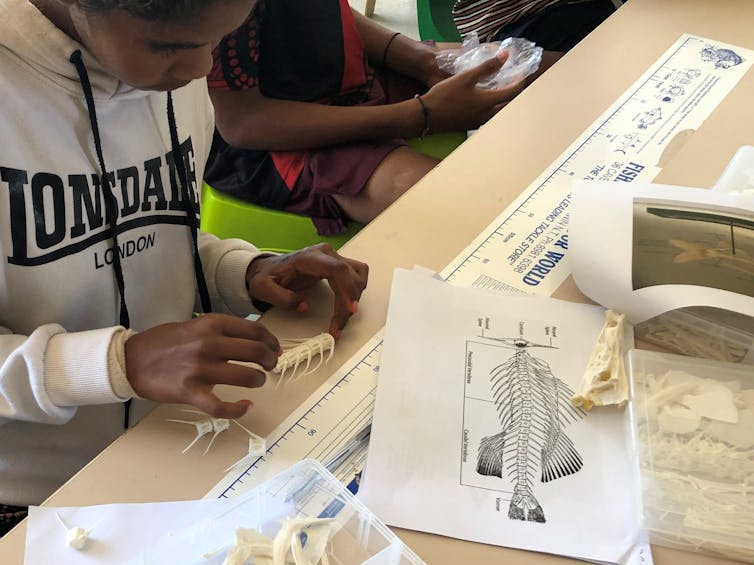

Local teachers interwove The Djenj Project throughout the class curriculum for the entire year. Researchers ran monthly workshops to teach children and rangers how to collect and interpret scientific information from fish, such as species, length, girth and weight, as well as the capture location and the fishing method used.

Fish were then processed to collect otoliths (ear bones), and sometimes their entire skeletons. Otoliths provide valuable information about the fish’s life, such as its size, age, season of death, and the water conditions it lived in.

Elders shared traditional knowledge about fish and fishing methods with the children. They worked together to construct bone points to use as fish hooks. They also constructed traditional fish traps, which involved making string from plant fibre.

Groups made trips to the rock art (bim) sites, where Elders shared knowledge about djenj, and the children found, recorded and counted djenj images.

While the Elders shared their knowledge about the local waterways, water monitoring specialists provided training in testing water quality for rangers and children. Children also learnt about the importance of water quality to the health of all living things.

Woven throughout all activities was attention to Indigenous languages, with staff from the Bininj Kunwok Language Resource Centre creating a dedicated language booklet and app focused on djenj. This resource is helping with language maintenance and revitalisation in the Bininj community, as well as providing Balanda with the necessary terms to have productive discussions with Bininj about fish and water.

What we learnt

Students and rangers gained a new appreciation for how much we can learn from our environment. The project also reinforced the rights of Bininj to engage in water and fish management processes.

The project also laid a foundation for future skills and environmental awareness with children (many of whom will go on to join local ranger teams). They have learnt cultural and scientific knowledge about fish, water, archaeology and rock art.

As researchers, we have established modern fish reference collections we can use and have learnt about local traditional fishing methods and ecological knowledge.

The Djenj Project is a great example of how grass-roots projects can provide practical benefits for Aboriginal communities, while contributing to scientific research. The model of collaborative teaching and learning from each other can be customised to benefit other communities.

We are planning to do more projects like this in West Arnhem Land over the following years, investigating other species of plants and animals.

Morgan Disspain, Adjunct Researcher, Southern Cross University and Lynley Wallis, Associate Professor, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/images/Coffs-harbour_student-group_20220616_33.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/services/counselling/images/RS21533_English-College-Student_20191210_DSC_6961.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/scholarships/images/STEPHANIE-PORTO-108-2.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/arts-and-humanities/images/RS20958_Chin-Yung-Pang-Andy_20190309__79I5562-960X540.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/experience/images/SCU-INTNL-STUDY-GUIDE-280422-256.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/dep-site-assets/component-library/screenshots/online-1X1.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Nigel-Andrew-gives-keynote-address-at-AES-Conference_2024-Nov-20-2000X973.jpg)

/885x0:4423x3538/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Jordan-Ivey-a-.jpg)

/834x0:4167x3333/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Lucas-Handley_Low-res-1a.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/grace-russell.png)

/256x0:1792x1536/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/12473932_10153551163870983_4881472587507230596_o.jpg)

/334x0:1667x1333/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Bee-research_19072014_DSC_9193.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Coral-reef_credit-Wikimedia-2000X973.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Various-degrees-of-bleaching-in-corals-next-to-each-other-at-Lizard-Island-on-Great-Barrier-Reef_credit-Melissa-Naugle-2000X973.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/cyril-callister.png)

/334x0:1667x1333/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/matthew-henry-yETqkLnhsUI-unsplash.jpg)